Stained glass

The term stained glass can refer to coloured glass as a material or to works made from it. Throughout its thousand-year history, the term has been applied almost exclusively to the windows of churches and other significant buildings. Although traditionally made in flat panels and used as windows, the creations of modern stained glass artists also include three-dimensional structures and sculpture.

Modern vernacular usage has often extended the term "stained glass" to include domestic leadlight and objets d'art created from lead came and copper foil glasswork exemplified in the famous lamps of Louis Comfort Tiffany.

As a material stained glass is glass that has been coloured by adding metallic salts during its manufacture. The coloured glass is crafted into stained glass windows in which small pieces of glass are arranged to form patterns or pictures, held together (traditionally) by strips of lead and supported by a rigid frame. Painted details and yellow stain are often used to enhance the design. The term stained glass is also applied to windows in which the colours have been painted onto the glass and then fused to the glass in a kiln.

Stained glass, as an art and a craft, requires the artistic skill to conceive an appropriate and workable design, and the engineering skills to assemble the piece. A window must fit snugly into the space for which it is made, must resist wind and rain, and also, especially in the larger windows, must support its own weight. Many large windows have withstood the test of time and remained substantially intact since the late Middle Ages. In Western Europe they constitute the major form of pictorial art to have survived. In this context, the purpose of a stained glass window is not to allow those within a building to see the world outside or even primarily to admit light but rather to control it. For this reason stained glass windows have been described as 'illuminated wall decorations'.

The design of a window may be non-figurative or figurative; may incorporate narratives drawn from the Bible, history, or literature; may represent saints or patrons, or use symbolic motifs, in particular armorial. Windows within a building may be thematic, for example: within a church - episodes from the life of Christ; within a parliament building - shields of the constituencies; within a college hall - figures representing the arts and sciences; or within a home - flora, fauna, or landscape.

Manufacture

Glass production

From the 10th or 11th century, when stained glass began to flourish as an art, glass factories were set up where there was a ready supply of silica, the essential material for glass manufacture. Silica requires very high heat to become molten, something furnaces of the time were unable to achieve. So materials needed to be added to both modify the silica network to allow the silica to melt at a lower temperature (potash, soda, lead), and then to rebuild the weakened network (lime) and make the glass more stable. Glass is colored by adding metallic oxides while it is in a molten state. Copper oxides produce green, cobalt makes blue, and gold produces red glass. Much modern red glass is produced using copper, which is less expensive than gold and gives a brighter, more vermilion shade of red. Glass colored while in the clay pot in the furnace is known as pot metal glass, as opposed to flashed glass.

Cylinder glass or Muff Using a blow-pipe, a "gather" (glob) of molten glass is taken from the pot heating in the furnace. The gather is formed to the correct shape and a bubble of air blown into it. Using metal tools, molds of wood that have been soaking in water, and gravity, the gather is manipulated to form a long, cylindrical shape. As it cools, it is reheated so the manipulation can continue. During the process, the bottom of the cylinder is removed. Once brought to the desired size it is left to cool. One side of the cylinder is opened. It is put into another oven to quickly heat and flatten it, and then placed in an annealer to cool at a controlled rate, making the material more stable. "Hand-blown" cylinder (also called muff glass) and crown glass were the types used in ancient stained-glass windows.

Crown glass This hand-blown glass is created by blowing a bubble of air into a gather of molten glass and then spinning it - by hand or on a table that revolves rapidly like a potter's wheel. The centrifugal force causes the molten bubble to open up and flatten. It can then be cut into small sheets. Glass formed this way can be both colored and used for stained-glass windows, or uncolored as seen in small paned windows in 16th and 17th century houses. Concentric, curving waves are characteristic of the process. The center of each piece of glass, known as the "bull's-eye", receives less force during spinning, so it remains thicker than the rest of the sheet. It also has the distinctive lump of glass left by the "pontil" rod, which holds the glass as it is spun out. This lumpy, refractive quality means the bulls-eyes are less transparent, but they have still been used for windows, both domestic and eccliesiastical. Crown glass is still made today, but not on a large scale.

Rolled glass Rolled glass (sometimes called "table glass") is produced by pouring molten glass onto a metal or graphite table and immediately rolling it into a sheet using a large metal cylinder, similar to rolling out a pie crust. The rolling can be done by hand or machine. Glass can be "double rolled", which means it is passed through two cylinders at once to yield glass of a certain thickness (approximately 1/8")(similar to the clothes wringers on early washing machines.) Glass made this way is never fully transparent, but doesn't necessarily have much texture. It can be pushed and tugged while molten for certain effects. For distinct textures the metal cylinder can be imprinted with a pattern that is pressed into the molten glass as it passes through the rollers. The glass is then annealed. Rolled glass was first commercially produced around the mid-1830s and is widely used today. It is often called cathedral glass, but this has nothing to do with medieval cathedrals, where the glass used was hand-blown.

Flashed glass Architectural glass must be at least 1/8 of an inch to survive the push and pull of typical wind load. In order to make RED glass, the ingredients used must be of a certain concentration, or the color won’t develop, but the resulting color is so concentrated, that if a sheet were made that is 1/8” thick, little light could actually pass through it – it would look black. So another method is usually used for making red glass, where most of the body of the glass is clear or a colored tint. This lightly-colored molten gather is dipped into a pot of molten red glass, forming a laminate that is then blown into a sheet of glass using either the cylinder (muff) or the crown technique. Once the solution was found for making red glass, other colors were also made this way. A great advantage is that the double-layered glass can be engraved or abraded to reveal the clear or tinted glass below. The method allows rich detailing and patterns to be achieved without needing to add more lead-lines, giving artists greater freedom in their designs. A number of artists have embraced the possibilities flashed glass gives them. For instance, 16th century heraldic windows relied heavily on a variety of flashed colors for their intricate crests and creatures. In the medieval period the glass was “abraded” (ground off), later HF acid was used to remove the flash in a chemical reaction (a very dangerous technique) and in the 19th century sandblasting started to be used.

Modern production of traditional glass There are a number of glass factories, notably in Germany, USA, England, France, Poland and Russia, which produce high-quality glass, both hand-blown (cylinder, muff, crown) and rolled glass (cathedral and opalescent). Modern stained-glass artists have a number of resources to use and the work of centuries other artists to dialogue with as they continue the tradition, but in new ways.

Creating stained glass windows

- The first stage in the production of a window is to make, or acquire from the architect or owners of the building, an accurate template of the window opening that the glass is to fit.

- The subject matter of the window is determined to suit the location, a particular theme, or the whim of the patron. A small design called a Vidimus is prepared which can be shown to the patron.

- A traditional narrative window has panels which relate a story. A figurative window could have rows of saints or dignitaries. Scriptural texts or mottoes are sometimes included and perhaps the names of the patrons or the person as whose memorial the window is dedicated. In a window of a traditional type, it is usually at the discretion of the designer to fill the surrounding areas with borders, floral motifs and canopies.

- A full sized cartoon is drawn for every "light" (opening) of the window. A small church window might typically be of two lights, with some simple tracery lights above. A large window might have four or five lights. The east or west window of a large cathedral might have seven lights in three tiers with elaborate tracery. In Medieval times the cartoon was drawn straight onto a whitewashed table, which was then used for cutting, painting and assembling the window.

- The designer must take into account the design, the structure of the window, the nature and size of the glass available and his or her own preferred technique. The cartoon is then be divided into a patchwork as a template for each small glass piece. The exact position of the lead which holds the glass in place is part of the calculated visual effect.

- Each piece of glass is selected for the desired colour and cut to match a section of the template. An exact fit is ensured by grozing the edges with a tool which can nibble off small pieces.

- Details of faces, hair and hands can be painted onto the inner surface of the glass in a special glass paint which contains finely ground lead or copper filings, ground glass, gum arabic and a medium such as wine, vinegar or (traditionally) urine. The art of painting details became increasingly elaborate and reached its height in the early 20th century.

- Once the window is cut and painted, the pieces are assembled by slotting them into H-sectioned lead cames. The joints are then all soldered together and the glass pieces are stopped from rattling and the window made weatherproof by forcing a soft oily cement or mastic between the glass and the cames.

- Traditionally, when the windows were inserted into the window spaces, iron rods were put across at various points, to support the weight of the window, which was tied to the rods by copper wire. Some very large early Gothic windows are divided into sections by heavy metal frames called ferramenta. This method of support was also favoured for large, usually painted, windows of the Baroque period.

- From 1300 onwards, artists started using silver stain which was made with silver nitrate. It gave a yellow effect ranging from pale lemon to deep orange. It was usually painted onto the outside of a piece of glass, then fired to make it permanent. This yellow was particularly useful for enhancing borders, canopies and haloes, and turning blue glass into green glass for green grass.

- By about 1450 a stain known as Cousin's rose was used to enhance flesh tones.

- In the 1500s a range of glass stains were introduced, most of them coloured by ground glass particles. They were a form of enamel. Painting on glass with these stains was initially used for small heraldic designs and other details. By the 1600s a style of stained glass had evolved that was no longer dependent upon the skilful cutting of coloured glass into sections. Scenes were painted onto glass panels of square format, like tiles. The colours were annealed to the glass and the pieces were assembled into metal frames.

- In modern windows, copper foil is now sometimes used instead of lead. For further technical details, see Lead came and copper foil glasswork.

- In the late 19th and 20th centuries there have been many innovations in techniques and in the types of glass used. Many new types of glass have been developed for use in stained glass windows, in particular Tiffany glass and slab glass.

Technical details

Maquette by Heaton, Butler and Bayne, 19th century English manufacturers |

Exterior of a window at Sé Velha de Coimbra, Portugal, showing a modern steel armature |

A set of glaziers' tools |

Skilled glass cutting and leading in a 19th century window at Meaux Cathedral, France |

Thomas Becket window from Canterbury showing the pot metal and painted glass, lead H-sectioned cames, modern steel rods and copper wire attachments |

Colours and mediums for painting on glass |

A palette and tools to prepare colours for painting on glass |

A small panel by G. Owen Bonawit at Yale University, c.1930, demonstrates grisaille glass painting enlivened with silver stain. |

European panel, 1564, with typical painted details, extensive silver stain, Cousin's rose on the face, and flashed ruby glass with abraded white motif |

Detail from a 19th or 20th century window in Eyneburg, Belgium, showing detailed polychrome painting of face. |

History

Origins

Coloured glass has been produced since ancient times. Both the Egyptians and the Romans excelled at the manufacture of small coloured glass objects. The British Museum holds two of the finest Roman pieces, the Lycurgus Cup, which is a murky mustard colour but glows purple-red to transmitted light, and the Portland vase which is midnight blue, with a carved white overlay.

In Early Christian churches of the 4th and 5th centuries there are many remaining windows which are filled with ornate patterns of thinly-sliced alabaster set into wooden frames, giving a stained-glass like effect. Evidence of stained glass windows in churches and monasteries in Britain can be found as early as the 7th century. The earliest known reference dates from 675 CE when Benedict Biscop imported workmen from France to glaze the windows of the monastery of St Peter which he was building at Monkwearmouth. Hundreds of pieces of coloured glass and lead, dating back to the late 7th century, have been discovered here and at Jarrow.[1] Stained glass was also used by Islamic architects in Southwest Asia by the 8th century, when the alchemist Jābir ibn Hayyān, in Kitab al-Durra al-Maknuna, gives 46 original recipes for producing coloured glass and describes the production of cutting glass into artificial gemstones.[2]

A perfume flask from 100 BCE-200 CE |

The Portland Vase, a rare example of Roman flashed glass |

An alabaster window in Orvieto Cathedral, Italy |

Stained glass in the Nasir al-Mulk mosque in Shiraz, Iran |

Medieval glass

For further infornation about stained glass technology:

Stained glass, as an art form, reached its height in the Middle Ages when it became a major pictorial form and was used to illustrate the narratives of the Bible to a largely illiterate populace.

In the Romanesque and Early Gothic period, from about 950 AD to 1240 AD, the untraceried windows demanded large expanses of glass which of necessity were supported by robust iron frames, such as may be seen at Chartres Cathedral and at the eastern end of Canterbury Cathedral. As Gothic architecture developed into a more ornate form, windows grew larger, affording greater illumination to the interiors, but were divided into sections by vertical shafts and tracery of stone. The elaboration of form reached its height of complexity in the Flamboyant style in Europe and windows grew still larger with the development of the Perpendicular style in England.

Integrated with the lofty verticals of Gothic cathedrals and parish churches, the glass designs became more daring. The circular form, or rose window developed in France from relatively simple windows with pierced openings through slabs of thin stone to wheel windows, as exemplified by that in the West front of Chartres Cathedral, and ultimately to designs of enormous complexity, the tracery being drafted from hundreds of different points, such as those at Sainte-Chapelle, Paris and the "Bishop's Eye" at Lincoln Cathedral.

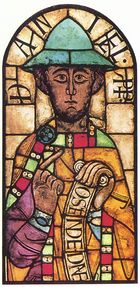

Daniel from Augsburg Cathedral, early 12th c. One of the oldest examples in situ. |

Detail of a 13th-century window from Chartres Cathedral |

Detail of a window of St George by Hans Acker (1440) in Ulm Minster, Germany |

Christ in Majesty from Strasbourg Cathedral |

The North Transept windows from Chartres Cathedral |

The Poor Man's Bible window at Canterbury Cathedral, 13th c. |

The west window of York Minster |

The rose window from Sainte-Chapelle, 15th c. |

The Renaissance and Reformation

In Europe, stained glass continued to be produced with the style evolving from the Gothic to the Classical style, which is widely represented in Germany, Belgium and the Netherlands, despite the rise of Protestantism. In France, much glass of this period was produced at the Limoges factory, and in Italy at Murano, where stained glass and faceted lead crystal are often coupled together in the same window. Ultimately, the French Revolution brought about the neglect or destruction of many windows in France. At the Reformation, in England large numbers of Medieval and Renaissance windows were smashed and replaced with plain glass. The Dissolution of the Monasteries under Henry VIII and the injunctions of Oliver Cromwell against "abused images" (the object of veneration) resulted in the loss of thousands of windows. Few remain undamaged; of them the windows in the private chapel at Hengrave Hall in Suffolk are among the finest. With the latter wave of destruction the traditional methods of working with stained glass died and were not to be rediscovered in England until the early 19th century. See Stained glass - British glass, 1811-1918 for more details.

St Anne with the Virgin and a saint, Ablis, Yvelines, France, mid 16th century |

The Cleansing of the Temple by Dirk Crabeth (1567), Janskerk (Gouda), Netherlands |

_-_Foto_G._Dall'Orto_2_lug_2006_-_10.jpg) Renaissance window in the church of SS Giovanni and Paolo, Venice 16th century |

Ghent Cathedral, Belgium, 16th century |

Stained glass in the Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés, Paris |

Drawsko Pomorskie Church, a good example of heraldic glass |

Les Andelys, Normandy, 16th century |

Altenberg Cathedral, a colourless window in the style known as Grisaille with a small heraldic motif |

Revival in Britain

The Catholic revival in England, gaining force in the early 19th century, with its renewed interest in the medieval church brought a revival of church building in the Gothic style, claimed by John Ruskin to be "the true Catholic style". The architectural movement was led by Augustus Welby Pugin. Many new churches were planted in large towns and many old churches were restored. This brought about a great demand for the revival of the art of stained glass window making.

Among the earliest 19th century English manufacturers and designers are William Warrington and John Hardman of Birmingham whose nephew, John Hardman Powell, who had a commercial eye and exhibited works at the Philadelphia Exhibition of 1876, influencing stained glass in the United States of America. Other manufacturers include William Wailes, Ward and Hughes, Clayton and Bell, Heaton, Butler and Bayne and Charles Eamer Kempe. A Scottish designer, Daniel Cottier, opened firms in Australia and the US.

Detail, Apostles John and Paul, Hardman of Birmingham, 1861-67, typical of Hardman in its elegant arrangement of figures and purity of colour. St. Andrew's Cathedral, Sydney |

One of England's largest windows, the east window of Lincoln Cathedral, Ward and Nixon (1855), is a formal arrangement of small narrative scenes in roundels |

William Wailes. This window has the bright pastel colour, a wealth of inventive ornament and stereotypical gestures of windows by this firm. St Mary's, Chilham |

Clayton and Bell. A narrative window with elegant forms and colour which is both brilliant and subtle in its combinations. Peterborough Cathedral |

Revival in France

In France there was a greater continuity of stained glass production than in England. In the early 19th century most stained glass was made of large panes that were extensively painted and fired, the designs often being copied directly from oil paintings by famous artists. In 1824 the Sèvres Porcelain factory began producing stained glass to supply the increasing demand. In France many churches and cathedrals suffered despoilation during the French Revolution. During the 19th century a great number of churches were restored by Viollet-le-Duc. Many of France's finest ancient windows were restored at this time. From 1839 onwards much stained glass was produced that very closely imitates medieval glass, both in the artwork and in the nature of the glass itself. The pioneers were Henri Gèrente and Andre Lusson.[3] Other glass was designed in a more Classical manner, and characterised by the brilliant cerulean colour of the blue backgrounds (as against the purple-blue of the glass of Chartres) and the use of pink and mauve glass.

Detail of a "Tree of Jesse" window in Reims Cathedral designed in the 13th century style by L. Steiheil and painted by Coffetier for Viollet-le-Duc, (1861) |

St Louis administering Justice by Lobin in the painterly style. (1809) Church of St Medard, Thouars. |

A brilliantly-coloured window at Cassagnes-Bégonhès, Aveyron |

West window from Saint-Urbain, Troyes, (about 1900) |

Revival in Europe

During the mid to late 19th century, many of Germany's ancient buildings were restored, and some, such as Cologne Cathedral were completed in the medieval style. There was a great demand for stained glass. The designs for many windows were based directly on the work of famous engravers such as Albrecht Dürer. Original designs often imitate this style. Much 19th century German glass has large sections of painted detail rather than outlines and details dependent on the lead. The Royal Bavarian Glass painting Studio was founded by Ludwig I in 1827.[3] A major firm was Mayer of Munich which commenced glass production in 1860, and is still operating as Franz Mayer of Munich, Inc.. German stained glass found a market across Europe, in America and Australia. Stained glass studios were also founded in Italy and Belgium at this time.[3]

A painted memorial window, Castle Bodenstein, Germany, early 19th century |

One of five windows donated to Cologne Cathedral by Ludwig II |

Post-Reformation window in the Memorial Church, Speyer, Germany |

An early 20th century window in the 17th century style, St Maurice's Church, Olomouc, Czech Republic |

Innovations in the United States

Notable American practitioners include John La Farge (1835–1910) who invented opalescent glass and for which he received a US patent February 24, 1880, and Louis Comfort Tiffany (1848–1933), who received several patents for variations of the same opalescent process in November of the same year and is believed to have invented the copper foil method as an alternative to lead, and used it extensively in windows, lamps and other decorations.

|

Many of the distinctive types of glass invented by Tiffany are demonstrated within this single small panel including "fracture-streamer glass" and "drapery glass". |

Window by Louis Comfort Tiffany with opalescent glass, asymmetric design and casual combination of flashed, painted and pot metal glass within the formal framework of supporting bars |

The Holy City by Louis Comfort Tiffany (1905). This 58-panel window has brilliant red, orange, and yellow etched glass for the sunrise, with textured glass used to create the effect of moving water. |

John La Farge, The Angel of Help, North Easton, MA shows the use of tiny panes contrasting with large areas of flashed or opalescent glass. |

Innovations in Britain and Europe

Among the most innovative English designers were the Pre-Raphaelites, William Morris (1834–1898) and Edward Burne-Jones (1833–1898), whose work heralds Art Nouveau. Art Nouveau or Belle Epoch stained glass design flourished in France, and Eastern Europe, where it can be identified by the use of curvings sinous lines in the lead, and swirling motifs. In France it is seen in the work of Francis Chigot of Limoges. In Britain it appears in the refined and formal leadlight designs of Charles Rennie Macintosh.

|

David's charge to Solomon shows the strongly linear design and use of flashed glass for which Burne-Jones' designs are famous. Trinity Church, Boston, US, (1882) |

God the Creator by Stanisław Wyspiański, this window has no glass painting, but relies entirely on leadlines and skilful placement of colour and tone. Franciscan Church, Kraków (c.1900) |

Window by Alfons Mucha, Saint Vitus Cathedral Prague. |

Art Nouveau by Jacques Grüber, the glass harmonising with the curving architectural forms that surround it, Musée de l'École de Nancy (1904). |

Twentieth century

Many 19th-century firms failed early in the twentieth century as the Gothic movement had been superseded by newer styles. At the same time there were also some interesting developments where stained glass artists took studios in shared facilities. Examples include the Glass House in London set up by Mary Lowndes and A.J. Drury and An Túr Gloine in Dublin, which was run by Sarah Purser and included artists such as Harry Clarke.

A revival occurred in the middle of the century because of the desire to restore the thousands of church windows throughout Europe, destroyed as a result of bombing during the World War II. German artists led the way. Much work of the period is mundane and often was not made by its designers but industrially produced.

Other artists sought to transform an ancient art form into a contemporary one, sometimes using only traditional techniques but often exploring the medium of glass in different ways and in combination with different materials. The use of slab glass set in concrete was another 20th-century innovation. Gemmail, a technique developed by the French artist Jean Crotti in 1936 and perfected in the 1950s, is a type of stained glass where adjacent pieces of glass are overlapped, without using lead nervures to join the pieces, allowing for a greater diversity and subtlety of colour.[4][5] Many famous works by late 19th- and early 20th-century painters, notably Picasso, have been reproduced in gemmail.[6] A major exponent of this technique is the German artist Walter Womacka.

Among the early well-known 20th-century artists who experimented with stained glass as an Abstract art form were Theo van Doesburg and Piet Mondrian. In the 1960s and 70s the Expressionist painter Marc Chagall produced designs for many stained glass windows that are intensely coloured and crammed with symbolic details. Important 20th-century stained glass artists include Douglas Strachan, Ervin Bossanyi, Louis Davis, Wilhelmina Geddes, Karl Parsons, Patrick Reyntiens, Ludwig Schaffrath, Johannes Shreiter, Judith Schaechter, Paul Woodroffe, Jean René Bazaine at Saint Séverin and the Loire Studio of Gabriel Loire at Chartres. The Luxus Keibel studio in Mexico specialises in domestic stained glass in both contemporary and 19th century styles. The west windows of England's Manchester Cathedral, by Tony Hollaway, are some of the most notable examples of symbolic work.

In the US, there is a 100-year-old trade organization, The Stained Glass Association of America, whose purpose is to function as a publicly recognized organization to assure survival of the craft by offering guidelines, instruction and training to craftspersons. The SGAA also sees its role as defending and protecting its craft against regulations that might restrict its freedom as an architectural art form. The current president is B. Gunar Gruenke of the Conrad Schmitt Studios. Today there are academic establishments that teach the traditional skills. One of these is Florida State University's Master Craftsman Program who recently completed a 30 ft high stained-glass windows installed in Bobby Bowden Field at Doak Campbell Stadium.

|

De Stijl abstraction by Theo van Doesburg, Netherlands (1917) |

Expressionist window by Marc Chagall, at All Saints' Church, Tudeley, Kent, UK |

Socialist Realism by Walter Womacka, Berlin, (c.1965) demonstrating the use of overlaid and laminated glass |

Abstract expressionism at Meiningen Catholic Church. |

Christ of the Eucharist designed by the monks of Buckfast Abbey, Devon, England, slab glass. |

One of four 64 metres (210 ft)-high stained glass panels, Rio de Janeiro Cathedral, Brazil |

Postmodernist symbolism, Tree of Life at Christinae church, Alingsås, Sweden. |

The Bald Eagle, a good example of the product of commercial studios working with traditional techniques, Dryden High School, USA |

Thin slices of agate set into lead and glass, Grossmünster, Zürich, Switzerland, by Sigmar Polke (2009) |

Window designed by Gerhard Richter using computer generated pixillation, Cologne Cathedral |

Combining ancient and modern traditions

|

Late 20th-c. window in the crypt of the Abbey of St Denis. The skilful adaptation of ancient tradition and modern style in a World Heritage Site. Fair use image |

Figurative design using the lead lines and minimal glass paint in the 13th century manner combined with the texture of Cathedral glass, Ins, Switzerland |

A figurative design employing polychrome painting of faces and monochrome painting of shadowed areas, artist Marko Jerman, Maribor Cathedral, Slovenia |

Buildings incorporating stained glass windows

Churches

.

Stained glass windows were commonly used in churches for decorative and informative purposes. Many windows are donated to churches by members of the congregation as memorials of loved ones. For more information on the use of stained glass to depict religious subjects, see Poor Man's Bible

- Important examples

- Cathedral of Chartres, in France- 11th-13th century glass

- Canterbury Cathedral, in England- 12th-15th century plus 19th-20th century glass

- York Minster, in England- 11th-15th century glass

- Sainte-Chapelle, in Paris, 13th-14th century glass

- Florence Cathedral, Italy, 15th century glass designed by Uccello, Donatello and Ghiberti

- St. Andrew's Cathedral, Sydney, Australia- early complete cycle of 19th century glass, Hardman of Birmingham.

- Coventry Cathedral, England, mid 20th century glass by various designers

- Brown Memorial Presbyterian Church, extensive collection of windows by Louis Comfort Tiffany

- Cathedral Basilica of the Assumption in Covington, Kentucky, USA

Synagogues

In addition to Christian churches, stained glass windows have been incorporated into Jewish temple architecture for centuries. Jewish Communities in the United States saw this emergence in mid-19th century, with such notable examples as the sanctuary depiction of the Ten Commandments in New York's Congregation Anshi Chesed. From the mid-20th century to the present, stained glass windows have been a ubiquitous feature of American synagogue architecture. Styles and themes for synagogue stained glass artwork is as diverse as their church counterparts. As with churches, synagogue stained glass windows are often dedicated by member families in exchange for major financial contributions to the institution.

Houses

Stained glass windows in houses were particularly popular in Victorian era and many domestic examples survive. In their simplest form they typically depict birds and flowers in small panels, often surrounded with machine-made cathedral glass, which, despite what the name suggests, is pale-coloured and textured. Some large homes have splendid examples of secular pictorial glass. Many small houses of the 19th and early 20th centuries have leadlight windows.

- Prairie style homes

- The houses of Frank Lloyd Wright

Public and commercial use of stained glass

Town halls, schools, colleges and other public buildings often incorporate stained glass or leadlighting.

- Public houses — In Britain, traditional pubs make extensive use of stained glass and leaded lights to create a comfortable atmosphere and retain privacy.

- Sculpture

See also

- Architectural glass

- Beveled glass

- British and Irish stained glass (1811-1918)

- Cathedral architecture of Western Europe

- Cathedral glass

- Float glass

- Glass art

- Glass beadmaking

- Glassblowing

- Lead came and copper foil glasswork

- Leadlight

- Poor Man's Bible

- Rose window

- Stained Glass Conservation

- Stained Glass Sculpture

- Tiffany glass

- Venetian glass

References

- ↑ Discovering stained glass - John Harries, Carola Hicks, Edition: 3 – 1996

- ↑ Ahmad Y Hassan, The Manufacture of Coloured Glass and Assessment of Kitab al-Durra al-Maknuna, History of Science and Technology in Islam.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Gordon Campbell, The Grove Encyclopedia of Decorative Arts, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-518948-5

- ↑ Le grand dictionnaire Québec government's online dictionary entry for gemmail (in French)

- ↑ Gemmail, Encyclopædia Britannica]

- ↑ [1], Gemmail Time

Further reading

- Lucy Costigan & Michael Cullen, Strangest Genius: The Stained Glass of Harry Clarke, The History Press, Dublin, 2010 ISBN 9781845889715

- Theophilus, On Divers Arts, trans. from Latin by John G. Hawthorne and Cyril Stanley Smith, Dover, ISBN 0-486-23784-2

- Elizabeth Morris, Stained and Decorative Glass, Doubleday, ISBN 0-86824-324-8

- Sarah Brown, Stained Glass- an Illustrated History, Bracken Books, ISBN 1-85891-157-5

- Painton Cowen, A Guide to Stained Glass in Britain, Michael Joseph, ISBN 0-7181-2567-3

- Lawrence Lee, George Seddon, Francis Stephens, Stained Glass, Spring Books, ISBN 0-600-56281-6

- Simon Jenkins, England's Thousand Best Churches, Allen Lane, the Penguin Press, ISBN 0-7139-9281-6

- Robert Eberhard, Church Stained Glass Windows, [2]

- Cliff and Monica Robinson, Buckinghamshire Stained Glass, [3]

- Stained Glass Association of America', History of Stained Glass, [4]

External links

- Harry Clarke the movie

- Harry Clarke Stained Glass windows

- Institute for Stained Glass in Canada, over 2200 photos; a multi-year photographic survey of Canada's stained glass heritage

- The Corning Museum of Glass, the world's best collection of art and historical glass; more than 45,000 objects trace 3,500 years of glassmaking history

- Preservation of Stained Glass

- Church Stained Glass Window Database recorded by Robert Eberhard, covering ~2800 churches in the southeast of England

- The Stained Glass Museum (Ely, England)

- Vidimus, an on-line magazine devoted to medieval stained glass.

- "Sacred Stained Glass". Glass. Victoria and Albert Museum. http://www.vam.ac.uk/collections/glass/glass_features/stained_glass/sacred_stained_glass/index.html. Retrieved 2007-06-16.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||